LEON DELACHAUX AND THE FILIAL BOND

Where motherhood is ubiquitous in the iconography of western art, the subject of fatherhood is rarely depicted. In Léon Delachaux’s work, women play a dominant role: mothers, women at work, socialites, young women, girls and even his wife Pauline, who modeled for him time and again. However, the images we do find of son, father and grandfather are filled with tenderness – images that undoubtedly echoed his own family life.

Born out of wedlock, Léon Delachaux was recognized by his parents Louis-Auguste and Mélanie a year later. Mélanie went on to bear four girls, none of whom survived. Both clockmakers, they were overwhelmed by misfortune. Distraught at not being able to feed his family, Louis-Auguste drowned himself in the Doubs River in 1855 when Léon was five years old.

Twenty years later it was his turn to become a father. After having settled for several years in his adopted hometown of Philadelphia, Léon married Pauline Noël. A year after the birth of their only child, Clarence, Léon discovered painting and enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

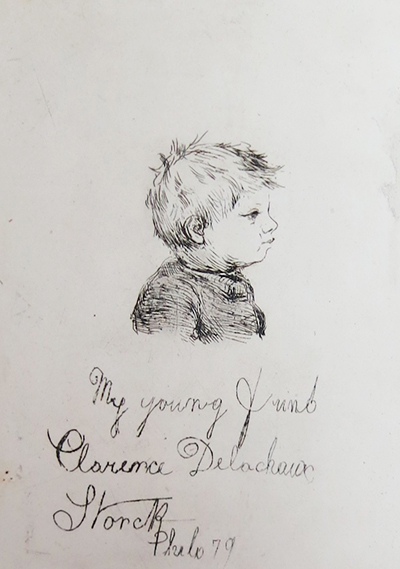

Christened Clarence-Léon, their beloved son is mentioned in Delachaux’s letters to his sculptor friend Carol Storck. In August 1882, he writes: “He has been very nice here lately […] He tells me to put a kiss in the letter for you. ” (1)

A month later he adds: “Clarence is splendid, a gaming devil, send you in photo. ” (2)

Storck executed an engraving of their dear child in 1879.

Fig. 1 : Carol Storck, “My young friend Clarence Delachaux Phila 79″, 1879,

etching, Bucharest, Romanian Academy, Department of Prints, inv. 20395.

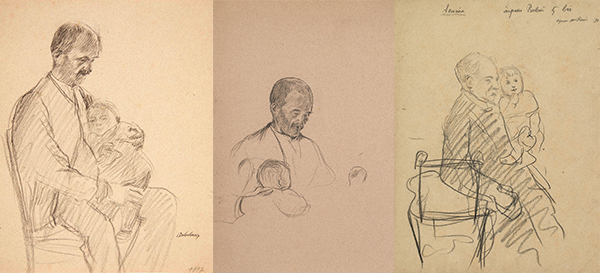

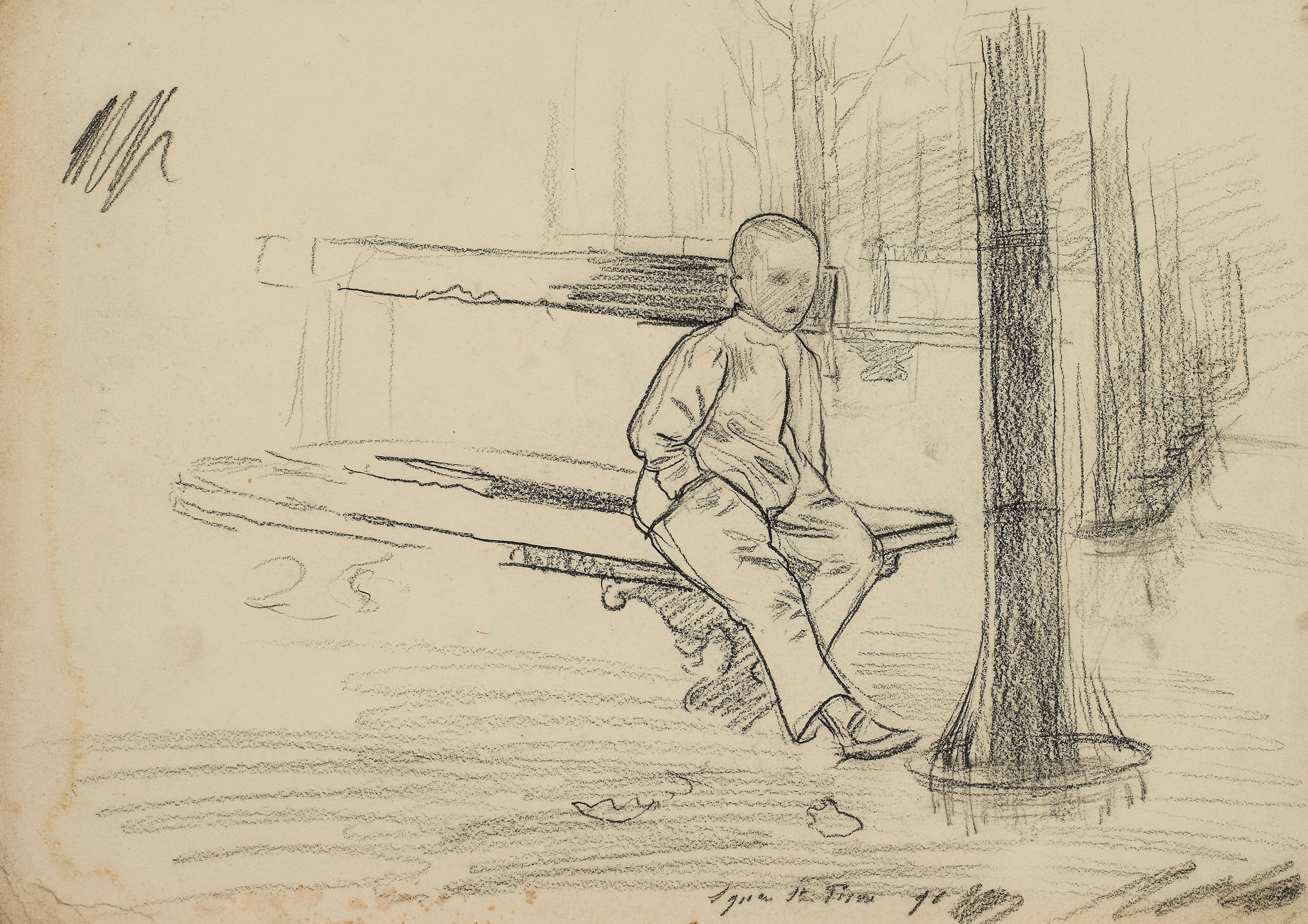

Numerous are the paintings and drawings that have come down to us depicting Clarence. Here are three of them using three different techniques.

Fig. 2 : Léon Delachaux, “Clarence Delachaux at six, Philadelphia”, 1881,

watercolor with gouache highlights on paper, 34.2 x 26.2 cm. Private collection.

© Stéphane Briolant

This one (Fig. 3), annotated affectionately Clarence my boy, dates from their return to France in 1884.

Fig. 3 : Léon Delachaux, “Clarence Delachaux, my boy”, 1884, pierre noire pencil. Private collection.

Fig. 4 : Léon Delachaux, “Portrait of Clarence Delachaux”, 1887, oil on panel, 39.5 x 31.8 cm. Private collection.

© Stéphane Briolant

Delachaux was also concerned with portraying the father, head of the household, as a figure of protection and tenderness.

In La famille du Cordonnier (The Cobbler’s Family) (Fig. 5), the representation of the father is centered on his profession; his wife watches in admiration, holding her young daughter asleep on her lap. It is the presence of the mother holding her child that establishes him as a family man. The composition is centered on the father’s hands while his figure, bathed in light, accentuates his role.

Fig. 5 : Léon Delachaux, “La famille du Cordonnier”, circa 1909,

oil on canvas, 73 x 60 cm, Saint-Amand-Montrond, musée Saint-Vic.

© Fonds de dotation Léon Delachaux – Photo Stéphane Briolant DR

Housed at the Museum of Art and History in Geneva, Elle dort déjà (She’s already asleep) (Fig. 6), depicts a young girl holding her little sister asleep on her lap. At their side, the father watches over them while he trusses asparagus. An art critic of the period points out that he “interrupts his work, hands on knees, holding his breath, enchanted at the sight of this infant, so well-behaved, so manageable, who deigns to go to sleep without a cry.” (3) The man’s watchful gaze solidifies the intimate bond between himself and his family. A sense of peace and warmth pervades the scene.

Fig. 6 : Léon Delachaux, “Elle dort déjà”, 1886,

oil on canvas, 59.2 x 68.5 cm, Geneva, Museum of Art and History.

© Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Ville de Genève (Inv 1886-0027)

Photo : Bettina Jacot-Descombes

In this interior scene at Aubigny-sur-Nère (Cher), the artist focuses on the relationship between a father and his children. A father shows his son and daughter how to shell an Easter egg (Fig. 7). With a jovial countenance, he smiles, happy to pass along his skills to his children, who are being particularly attentive. This powerful connection with childhood appears frequently throughout Delachaux’s work.

Fig. 7 : Léon Delachaux, “A Pâques(Easter Eggs)”, circa 1892,

oil on canvas, 46.1 x 55.7 cm, Neuchâtel, Museum of Art and History.

© Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Neuchâtel (Suisse)

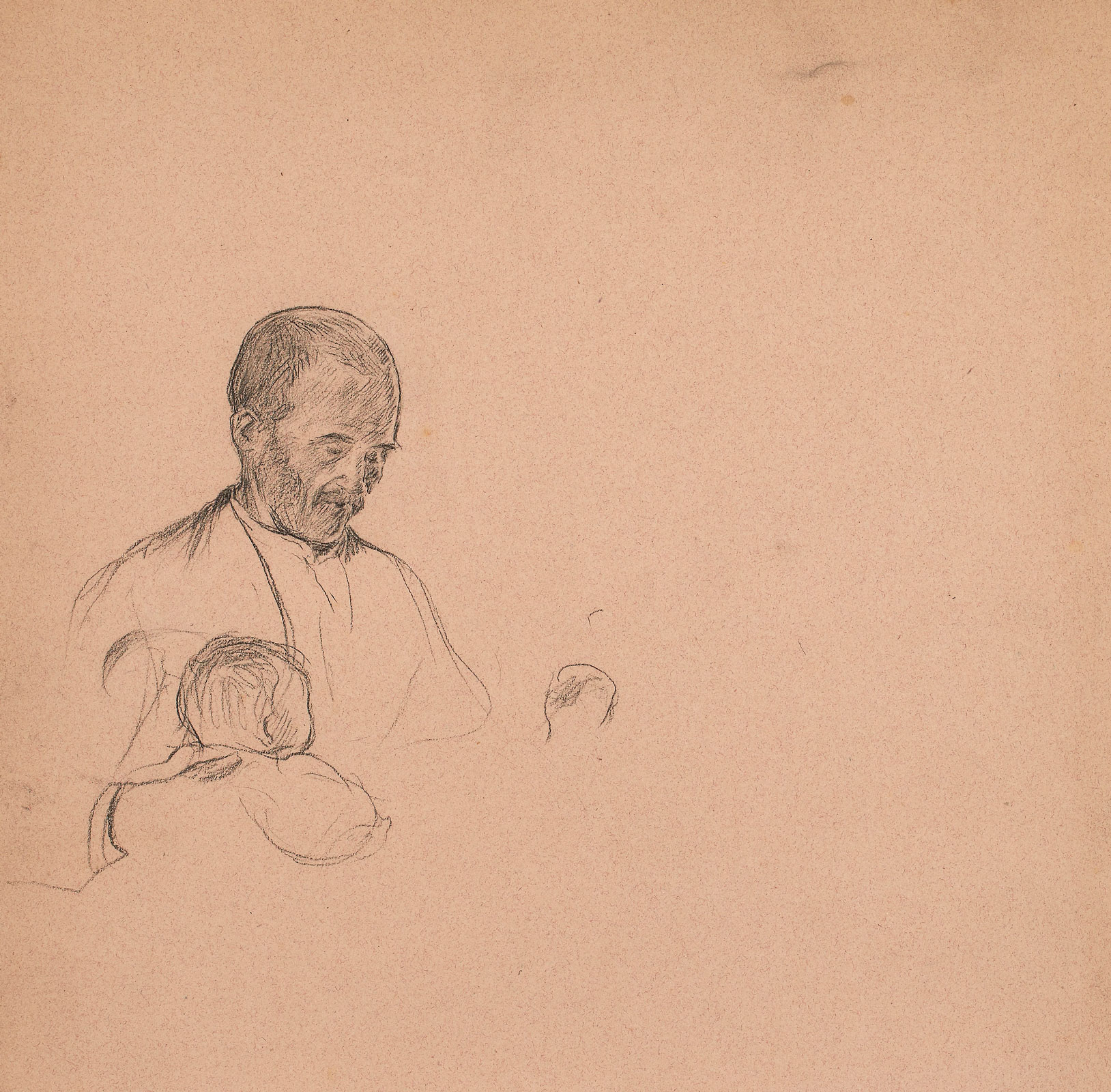

It is in his drawings that the artist reveals the full depth of fatherly love. In the Montmartre drawings shown here (Figs. 8, 9 and 10), we see a father, who, like the Madonna, holds his infant child close.

A sense of calm and serenity emerges from these stolen moments taken from life. They acknowledge the artist’s sense of tenderness.

Fig. 8 : Léon Delachaux, “Man holding a baby on his lap, study”, 1897, pierre noire pencil, 26.6 x 21 cm. Private collection.

Fig. 9 : Léon Delachaux, “Man sitting with a baby on his lap”, 1897, pierre noire pencil, 37.5 x 26.5 cm. Private collection.

Fig. 10 : Léon Delachaux, “Man holding his grandson in his arms”, 1898, pierre noire pencil, 32 x 24 cm. Private collection.

© Stéphane Briolant

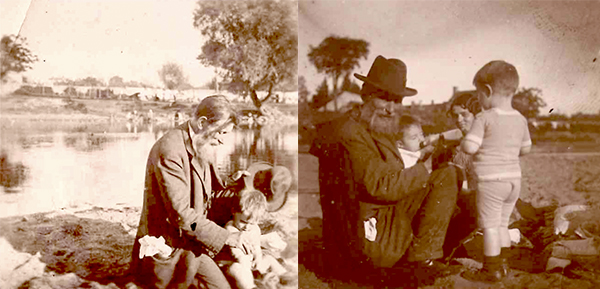

The artist continues this paternal focus once he becomes a grandfather, witnessed in these lines to his painter friend François Guiguet in June 1917:

“At the end of the month or at the beginning of September, I’m planning to go to Grez to see the whole family. It’s going to be exhausting and a ray of sunshine, as well as a great joy. Today I received photos of all the little devils in funny poses. They bring us all much joy.” (4)

These two snapshots (Figs. 11 and 12) in our possession were taken in 1914. Clarence had just purchased the large house in Grez, on the bank of the Loing River. However, after being drafted, he entrusted his family to his father who took them to his home in Saint-Amand-Montrond (Cher). Clarence’s two eldest, Philippe and Robert, found their grandfather to be naturally attentive and affectionate.

Fig. 11 : Léon Delachaux and his grandson, Philippe, at Saint-Amand-Montrond, 1914, photograph. Private collection.

Fig. 12 : Léon Delachaux bottle-feeding his grandson Robert under the watchful eye of Philippe and their nanny

at Saint-Amand-Montrond, 1914, photograph. Private collection.

© Stéphane Briolant

The premature death of his four sisters (5) undoubtedly had a lasting impact on the young Léon. As a child scarred by so many tragedies, he was able over a lifetime to regain what he had lost: a family. Unknowingly, he conveyed to us his strong desire to be united, responsible and surrounded by family.

-

(1) Bucharest, Romanian Academy, Department of Manuscripts, Letter from Léon Delachaux to Carol Storck, Philadelphia, August 1882. S5 (5) CCCXXXIV

(2) Bucharest, Romanian Academy, Department of Manuscripts, Letter from Léon Delachaux to Carol Storck, Philadelphia, September 16, 1882. S5 (6) CCCXXXIV

(3) W. S., “Salon suisse des beaux-arts et des arts décoratifs” in Le Journal de Genève, no. 238, October 9, 1886.

(4) Corbelin, Maison Ravier, Letter from Léon Delachaux to François Guiguet, Saint-Amand-Montrond, June 7, 1917.

(5) Valérie-Eugénie (1851-1860) at the age of nine; Léonie-Athénaïse (1853-1854) at the age of one; Marie-Bertha (1854-1854) at the age of two months; Adèle-Athénaïse (1855-1860) at the age of five.

LEON DELACHAUX’S INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS: AMERICA, EUROPE, ASIA

« Art can be made great anywhere, it is not the place, it is the man »

Letter to Carol Storck, July 30, 1881

April 2021: At the time of writing, art museums and events have become inaccessible. Somewhat frustrated to be unable to visit or travel, the Endowment Fund’s art historians have chartered the course of the artist’s works, taking us around the world with them, and giving us a broader insight into the commercial and artistic routes of a man who took pride in his work and exhibiting it.

Conceived and developed by Corisande Evesque, one of the Fund’s art historians, the interactive map of Delachaux’s exhibition history is updated as new findings are made. Illustrating the status of our research on this subject, it shines new light on the life and work of the artist and enables us to view Delachaux’s commitment to international salons, galleries and curators. From 1879 to 1918, he developed an impressive national and international network, taking part in more than 200 exhibitions worldwide.

We invite you to follow in his footsteps.

Delachaux was twenty-six when, as a visitor to the influential Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, he discovered his passion for painting. It was there that he first encountered the Barbizon School of painters, Bartholdi’s torch for the future Statue of Liberty or Jules Dalou’s Brodeuse.

His exhibiting career lasted almost forty years, from 1879 in Philadelphia – date of his first known exhibition – until 1918 in Paris, shortly before his death. From the start of his career in North America we witness the lively and colorful bourgeois interiors and portraits of Black Americans. Once back in France, he adapts his style to the simplicity of peasant life, employing subtle and delicate tones. Throughout his career, he also proved to be an excellent portraitist.

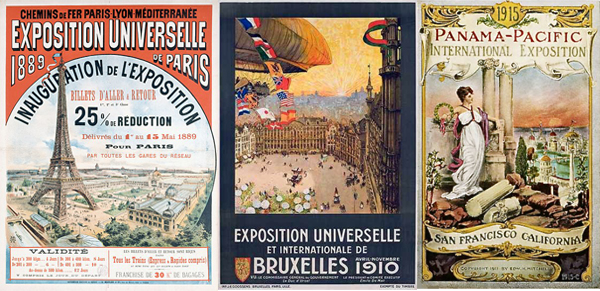

Delachaux obtained his U.S. citizenship in 1883 and began his exhibition career listed as an American national. Exhibiting yearly at the Salon des Artistes Français and then at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, he also partook in the World Fairs of Paris (1889 and 1900), Chicago (1893), Saint-Louis (1904), Brussels (1910), Ghent (1913) and San Francisco (1915).

His work crisscrossed France thanks to the dynamic momentum of the Sociétés des Amis des Arts. He also gained exposure elsewhere in Europe, through exhibits featuring French and international artists. From 1886 to 1903, he exhibited in group and traveling exhibitions organized by the Société Suisse des Beaux-Arts, commonly known as Turnus. We note his presence at exhibitions run by Société des Amis des Arts of Neuchâtel and La Chaux-de-Fonds – his family birthplace – as well as the Exposition nationale des Beaux-Arts in Bern and the Exposition municipale des Beaux-Arts in Geneva. In Switzerland alone, Delachaux took part in close to 50 shows, second in number only to France.

« Le Crux Ave à Pâques », 1887, oil on canvas, Kunsthaus Zürich (Switzerland).

Exhibitions: 1887, Paris, Salon des Artistes Français – 1888, New York, Prize Fund Exhibition

1888, Philadelphia, PAFA 58th annual exhibition – 1889, Zurich, Schaffhausen and Basel, Turnus

© 2016, Kunsthaus Zürich (Suisse)

In 1902 his work was sent to Asia, where it was shown in Hanoi in an exhibit to commemorate the new capital of French Indochina. His art traveled all the way to South America in 1910, where his Costurera was shown at the Exposición Internacional de Bellas Artes in Santiago de Chile, and where it still remains today.

Even though Delachaux achieved true recognition in his time, he, like many talented naturalist painters, has been forgotten over the last century. His success can be measured by the sheer number of exhibitions in which he took part, the works acquired by the French government during his lifetime and those present in public collections worldwide, yet his work still remains under-recognized today.

DELACHAUX, MONTMARTRE, WORKS ON PAPER, 1888 – 1919

“M. Delachaux, a colorist, even when using a pencil”

Journal de Genève, 12 February 1889

In 1888, the painter Léon Delachaux moved to rue Durantin, at the foot of the Butte Montmartre in Paris.

He kept this modest pied-à-terre until his death, using it as his studio and, later, as a home base between travels.

He integrated village life where families of artisans and laborers coexisted with the artists of the Bateau-Lavoir. Clarence, his only son, was a student at the lycée Chaptal. Delachaux exhibited in France, Switzerland, Europe and the United States. Yet he felt drawn to the Louvre, as he explained in a letter to Théogène Chavaillon, his artist friend from Saint-Amand: “I have begun to feel the need to see the Louvre again, it is so beautiful and one feels so at home in those beautiful rooms among those masterpieces.” (1)

Léon Delachaux’s entire body of work bears witness to a master of intimacy. His works on paper and his sketchbooks reveal an unremitting attention to that which is alive and emotionally moving. Known to us are his numerous drawings depicting his favorite spots – streets or public squares – where he sketched relentlessly all that he witnessed: conversations, family scenes, snapshots in time. Even when taken ill he continued to draw: “I’m still confined to my dreary studio and I spend my time drawing!” (2)

Fully displayed in the sketches created at the square Saint-Pierre in the 1890s are the artist’s close observational skills and his preference for life’s ordinary subjects:

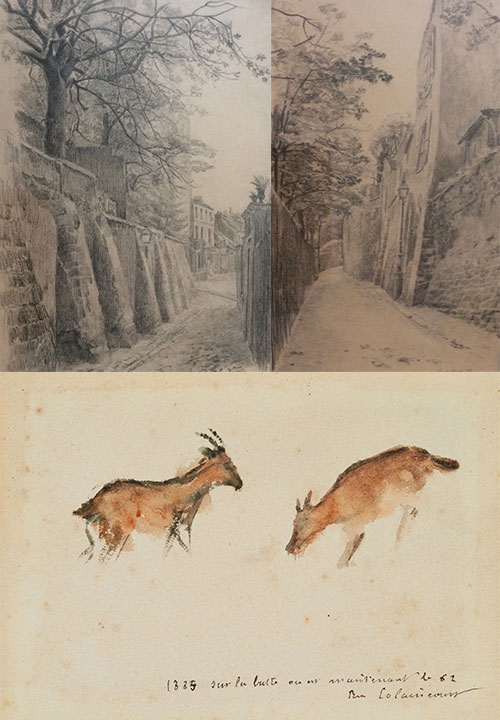

Léon Delachaux’s interest in meticulous representation of the urban landscape can be seen in his highly successful drawings depicting the rue Saint-Vincent; its mighty terraced walls have been home to the Clos-Montmartre vineyard since the tenth century. Other scenes depict the rue de l’Abreuvoir (drinking trough), which the French Romantic poet Gérard de Nerval described in 1854: “What charmed me most in this small space shaded by the tall trees of the château des Brouillards, was […] the proximity of the drinking trough, which, in the evening, came to life with the sight of horses and dogs being washed in it.”

His watercolor sketches of goats are a reminder that Montmartre was once in the countryside.

Léon Delachaux (1850-1919)

“La Rue Saint-Vincent I” et “La Rue Saint-Vincent II”, 1896. Drawings, 38 x 24 cm et 39 x 29 cm.

“Study of goats, Montmartre”, 1885. Watercolor and pencil on laid paper, 10,4 x 15,5 cm.

Private Collection

In 1889 – year of the Paris Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair) – Buffalo Bill came to France with hundreds of people and horses to perform his “Wild West” show and set up camp on the Butte Montmartre. A watercolor by Delachaux, dedicated to his friend François Guiguet (1860-1937), depicts this historic site, indicated by the handwritten note on the back: “View from rue Caulaincourt where Buffalo [Bill], the bandit, stayed, before construction of the set.”

Léon Delachaux (1850-1919), “Landscape, Souvenir de la Butte (Souvenir of Montmartre)”

Watercolor on paper, 25,5 x 36 cm. Private Collection

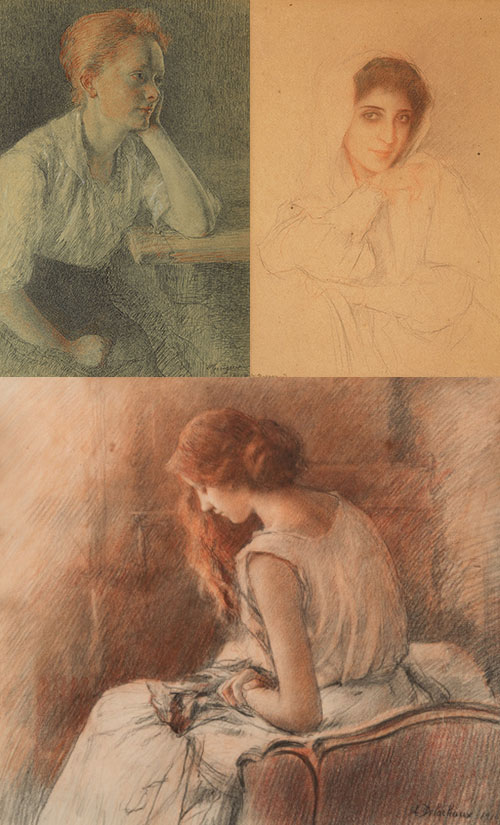

François Guiguet and Léon Delachaux, both Montmartre residents, were neighbors and became friends. They corresponded on a regular basis until 1918. Their letters reveal the importance they attached to drawing. They exhibited together at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, hailed by critics: “Mr. Guiguet, […] such truth in interpretation, which at times borders on indiscretion. His drawings in red chalk are among the most beautiful in the contemporary school, along with those of Dagnan-Bouveret and Mr. Delachaux.” (3) et (4)

François Guiguet (1860-1937), “Jeanne pensive (Pensive woman)”, 1918,

red and black chalk on paper, 37 x 26,5 cm. Private Collection

Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852-1929), “Femme au voile (Veiled woman)”,

red and black chalk on paper, 27 x 19 cm. Private Collection

Léon Delachaux (1850-1919), “Jeune fille pensive de profil (Pensive young woman, profile)”, 1916,

red and black chalk on paper, 30 x 35 cm. Private Collection

.

.

(1) : Letter from Léon Delachaux to Théogène Chavaillon, from Saint-Amand-Montrond, on 18 January 1906. Chavaillon Archives.

(2) : Lettre from Léon Delachaux to Théogène Chavaillon, from Paris, rue Durantin, on 8 or 9 March 1902. Chavaillon Archives.

(3) : Léandre Vailéat, « Au sujet des Salons de 1912 », Le Correspondant, 1912, 84ème année, tome 247, Paris, Bureaux du Correspondant, p. 71.

(4) Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852-1929) was Léon Delachaux’s master from 1883 to 1884.

/ / /

/ / /

/ / /

JAN. 27 1919 > JAN. 27 2019 : CENTENNIAL OF LEON DELACHAUX’S DEATH

Celebrating the one-hundredth anniversary of Léon Delachaux’s death also means paying tribute to the places he inhabited. The painter spent the longest periods of time in Montmartre and Saint-Amand-Montrond (Cher). His passage is now etched in stone.

On September 21, 2019, under the autumn sun, the Endowment Fund inaugurated a commemorative plaque marking Léon Delachaux’s home-studio at 65 avenue Jean-Jaurès in Saint-Amand-Montrond, where the artist lived on a regular basis from 1900 to 1919. There to unveil the plaque in unison were Madame Menonville, the property’s current owner; Thierry Vinçon, mayor of Saint-Amand-Montrond; Marie Delachaux, President of the Léon Delachaux Endowment Fund and Guillaume Delachaux, her brother and the artist’s great-grandson. After the ceremony, the Saint-Vic museum hosted a cocktail party among its holding of sixteen works by Léon Delachaux.

On September 28, 2019, the Fund placed a plaque at 20 rue Durantin in Montmartre, this time commemorating Léon Delachaux’s Parisian sojourn. It is here, just a few steps from the Bateau Lavoir, that Léon and Pauline settled in 1888, enabling their only son Clarence to pursue his studies at the lycée Chaptal. Delachaux joined Montmartre’s bohemian community, mingling with Guido Sigriste, Luigi Chialiva, friend of Edgar Degas, and François Guiguet. The family remained attached to Montmartre, alternating between Saint-Amand-Montrond until Delachaux’s death in 1919.

Léon Delachaux is now part of the public sphere. This would not have been possible without the help and benevolence of the Musée Saint-Vic team, the properties’ owners, officials and their deputies in charge of cultural affairs. Once again, we would like to thank them warmly.

Photography : © Cécile Burban

/ / /

/ / /

/ / /

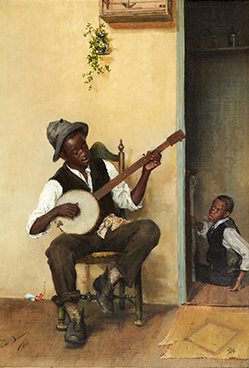

EXHIBITION: “THE BANJO PLAYER” AT POINTE-A-PITRE

Lending artworks for exhibition purposes is a beneficial means to introduce Léon Delachaux and one of the Endowment’s objectives – the mission of its Lending Committee is to arrange such opportunities.

This past summer, it was able to provide The Banjo Player – one of Delachaux’s most emblematic works – the chance to travel across the Atlantic to be displayed in the magnificent exhibition organized by the Mémorial ACTe in Pointe-à-Pitre: “Le modèle noir: de Géricault à Picasso ” (“The Black Model: from Géricault to Picasso”). In this symbolic site, a luminous homage is paid to those victims of human insanity, those who lost hope and their lives, those who survived and stood up for liberty.

We will cherish the memory of the hospitality extended to us by Jacques Martial, President of Mémorial ACTe and curator of the exhibition. Quoting Aimé Césaire, his informed and powerful commentary introduced us to the exhibit’s leading figures.

Jacques Martial, President of Mémorial ACTe,

and Marie Delachaux,

President of the Léon Delachaux Endowment Fund,

in front of The Banjo Player by Léon Delachaux, Oct. 11, 2019

The Banjo Player, in cadence, introduces the exhibition’s section “En scène” (“In the spotlight”) highlighting the Afro-American rhythm and movement that revolutionized the United States and Europe. Jazz and Josephine Baker made the world dance and changed the vision of man.

Rubbing shoulders with Alexandre Dumas, Joseph (male black model for Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa), the splendid African Venus by Cordier, Jean-Pierre Schneider’s contemporary homage to Manet’s Olympia and many others, The Banjo Player, in this way, becomes an integral part of history and acquires a new complexity. We were touched to learn that the Guadeloupean public identified with The Banjo Player as a close family member.

Léon Delachaux, “The Banjo Player”, 1881

Oil on canvas, 42,5 x 28,8 cm

Léon Delachaux Endowment Fund Collection

© Stéphane Briolant

After its success at the Wallach Art Gallery in New York and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the exhibition Le modèle noir completed its circuit at the Mémorial ACTe in Pointe-à-Pitre on December 29, 2019. The Léon Delachaux Endowment Fund would once again like to thank Jacques Martial and his team for welcoming the Banjo Player on its museum walls.

/ / /

/ / /

/ / /

EXHIBITION: A DELACHAUX ON EXHIBIT AT THE FOURNAISE MUSEUM!

The exhibition, L’âge de raison vu par les peintres au XIXe siècle (The Age of Reason seen through the eyes of nineteenth-century painters), is showing through November 4, 2018 at the Fournaise Museum.

The subject of childhood, spanning the ages of seven through twelve, is the focus of this exhibition, which presents works produced between 1830 and 1914. Delachaux hangs alongside paintings by Dehodencq, Lebasque, Muenier, Valadon and Bonvin.

The Léon Delachaux Endowment Fund is very pleased that The Affectionate Mother was among those paintings selected to illustrate a theme very dear to the artist, that of a happy childhood.

In 1883, Léon Delachaux painted Pauline and Clarence on the eve of their return to Europe. With the interest of a boy his age, the eight-year-old Clarence looks on as his mother, Pauline, repairs his toy sailing ship. Symbol of their imminent departure, the scale model ship displays the American flag. The title The Affectionate Mother, written in the hand of the artist on the back of the painting, conveys Delachaux’s feelings for his wife and son.

Anne Galloyer, curator of the Fournaise Museum in Chatou and Marie Delachaux, President of the Léon Delachaux Endowment Fund, before The Affectionate Mother.

The Affectionate Mother, 1883, oil on canvas, 46 x 36 cm. Private Collection.

Practical information:

L’Âge de raison vu par les peintres au XIXe siècle

Through November 4, 2018

Musée Fournaise - Ile des Impressionnistes - 78400 Chatou

+33 (0)1 34 80 63 22 – www.musee-fournaise.com

/ / /

/ / /

/ / /

DELACHAUX IN CHILE

In 1876, Léon Delachaux started at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia under the guidance of Thomas Eakins. Delachaux began showing his work in the United States in 1879 and continued to exhibit coast to coast until 1915.

He also, however, exhibited his work beyond San Francisco [and the borders of the United States]; his pictures travelled on to South America to be shown in the large international exhibitions held there in the early 1900s.

Léon Delachaux, La Lingère (Costurera), (detail). Chile – Santiago – Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes

One such exhibition was the Exposición Internacional del Centenario held in Santiago in 1910 to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the Chile’s independence. The Chilean journalist, Alberto Mackenna Subercaseaux, an intellectual of French descent, was one of the founders of the exhibition and its chief administrator. In his book Luchas por el Arte, he recounts his voyage to Europe and makes a case for bringing European and North American art to the Chilean public as a means to elevate national taste – an idea that, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was widely held among the Chilean elite.

Chile – Santiago – Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes

Of the 1600 foreign works exhibited, 65 works by French artists were acquired by the museum; the Comité permanent des Expositions françaises à l’étranger, a committee presided over by the painter Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), brokered the transaction.

La lingère (Costurera), was part of the acquisition.

Léon Delachaux, La Lingère (Costurera), c. 1909, oil on canvas, 63.5 x 51 cm. Chile – Santiago – Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes

Natalia Keller, head of research of the Department of Collections at Santiago’s Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, describes the piece in these terms:

“The seamstress sits in a humble interior, surrounded by everyday objects: bowls and jars arranged atop a chest of drawers, sewing accessories placed on a chair, and on the back wall, barely discernable, hang a large wall clock and mirror. The picture represents the archetype of the model housewife, and a woman’s role in society as defined by the authorities of the new Chilean republic at the beginning of the century.”

In January 2017, Marie Delachaux, President of the Léon Delachaux Endowment Fund, met with Natalia Keller at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes where she was shown her great-grandfather’s picture. The outcome of this meeting launched a partnership between Santiago and Paris.

Natalia Keller and Marie Delachaux, January 2017. Chile – Santiago – Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes

/ / /

/ / /

/ / /

PHILADELPHIA, BIRTH OF A PAINTER

It is in Philadelphia, City of Brotherly Love and capital of nineteenth-century American art, that Léon Delachaux discovers his vocation and starts a family.

Self-portrait with Overcoat (detail). Black chalk, 30 x 30 cm. Private Collection.

Portrait of Pauline with a Hat (detail), 1894. Pastel on paper mounted on canvas, 56 x 47 cm. Private Collection.

Portrait of Clarence Delachaux (detail), 1887. Oil on canvas, 39.5 x 31.8 cm. Private Collection.

Photos: Stéphane Briolant

Known for its quality of life and as a center for the arts, “Philly” is also home to the founding principals of a nation: the Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776) and the Constitution of the United States (1787).

Timeline:

In 1875, in Philadelphia, Léon Delachaux marries Marie-Apolline Noël, a French immigrant like himself, who gives birth to their only son, Clarence.

In 1876, Delachaux is recorded as a watchcase engraver. The Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition (World’s Fair) takes place the same year. It is here, at the age of 26, that he discovers painting.

He enrolls at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (P.A.F.A.).

A man, an artist is born.

From 1878 to 1880, Delachaux lives with his family in a studio at 1934 Locust Street, a studio he shares with another P.A.F.A. student, the Romanian sculptor Carol Stork. It is here that he paints using models.

From 1879 to 1886, Delachaux studies at the P.A.F.A. under the controversial Thomas Eakins, father of American Realism.

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA

Delachaux exhibits in the United States from 1880 to 1915: Louisville, KY; New York, NY; Boston, MA; Philadelphia, PA; Indianapolis, IN; Pittsburg, PA; Saint Louis, MI.

At the P.A.F.A. in Philadelphia, Delachaux exhibits in both permanent and special exhibitions.

Six of his works are exhibited together, thanks to Delachaux’s collector Harrison Earl, who makes a long-term loan of his collection to the P.A.F.A.

The Unfortunate Accident, circa 1880. Oil on canvas, 36.8 x 21.6 cm. Private Collection.

Photo: Stéphane Briolant

In 1883, Delachaux and his family return to France, thanks to his picture dealer who finances the voyage.

In return, the painter will send all his French pictures to Philadelphia. This explains why so many works by Delachaux are now in the United States.

Summer (detail), 1881. Oil on canvas, 56 x 51 cm. Private Collection.

The Affectionate Mother (detail), 1883. Oil on canvas, 45.7 x 38.7 cm. Private Collection.

Gray Day at the Bridge in Grez (detail), 1885. Oil on canvas, 40.01 x 60.33 cm. Private Collection.

Photos: Stéphane Briolant

Delachaux’s nationality has caused some confusion among art historians.

With reason: he is born in France of a Swiss father, becomes a naturalized American in 1883 and in 1907 recovers his French nationality while retaining the inalienable rights to his Swiss nationality!

In 1900, Delachaux buys a beautiful home with an art studio in Saint-Amand-Montrond, a small town in central France, where he spends the last twenty years of his life.

However, he continues to journey into the French countryside as well as to Paris and Grez-sur-Loing where his son Clarence and his family live.

Léon Delachaux dies in 1919. He is buried at Grez-sur-Loing, alongside his spouse.

English

English  Español

Español  Français

Français